- Home

- Dave Costello

Flying Off Everest Page 3

Flying Off Everest Read online

Page 3

He asked someone walking by, “Do you know where I can find the tourists?”

II

The Flying Sherpa

Sarangkot, Nepal,

November 2010—Approximately 2,925 Feet

“Run,” Babu said, and watched as his new friend, Lakpa, sprinted toward the steep drop-off 20 feet in front of him. Below lay the terraced rice fields of Sarangkot, a small hillside village located 2.5 miles north of Pokhara that’s not entirely unaccustomed to paragliders crashing into it. Pokhara is one of the best and most popular places in the world to go paragliding, and the crest of the hill above the small village of Sarangkot is the best and closest place to launch a paraglider from the city. On good days, when the sky is clear with a warm sun and no wind, the grassy hillside bustles with pilots and their tandem passengers and the sky above fills with a circling swarm of paragliders, rising up into the clouds and then sinking back down on the breeze. Beyond the fields to the south sits the growing expanse of the city and the dark blue of Lake Phewa.

Lakpa’s paraglider wing caught the air and quickly began to rise. The large, 40-plus-foot sail pulled back at him. A few more hurried steps and suddenly the ground was out from under his feet. He was flying—although not well, Babu observed. Lakpa didn’t actually know how to fly. Unlike the other pilots around him, who circled upward in the nearby thermal—a hot uprising of air beside the hill, like the swirling eddy that forms behind a rock in a river—Lakpa floated straight down toward the lake. He had flown only a handful of times before, first during a nine-day introduction course in Pokhara in 2009, and then again a few months later during a quick and mildly disastrous flight in the Khumbu, which resulted in him landing rather inelegantly in a tree. In Sarangkot he was the only pilot in the sky wearing a personal flotation device (PFD). Knowing he could land in the lake, Lakpa, who couldn’t swim, borrowed the PFD just in case he overshot his landing site on the shore.

Babu considered this as he watched his new friend descend, and wondered why Lakpa, a well-paid Sherpa who made his living climbing mountains, would ever want to fly. It is not normal, he was certain. Babu waited to see how the landing went before making any decisions about sharing his plans for Everest with Lakpa. He didn’t want a dead Sherpa on his conscience, certainly—but he also couldn’t help but wonder if Lakpa might just be crazy enough to help him with his idea to fly off the top of the world. After all, Lakpa had already told him that he wanted to fly off all of the peaks he regularly guided on. And the man had already climbed Everest. Three times.

Pokhara, Nepal,

November 2010—Approximately 2,625 Feet

A few hours earlier …

The city of Pokhara is in central Nepal. The town sits on the eastern shore of Phewa Tal, a large lake in Pokhara Valley, which is a widening of the Seti Gandaki Valley just south of the 26,545-foot Annapurna Massif—a broad, gleaming white band of the Himalaya rising up from the forested foothills just outside of town. The Seti Gandaki River runs through Pokhara, its churning waters flowing through deep, cavernous gorges, often right beneath the city. A single two-lane mountain road called the Prithvi Highway follows the meandering banks of the nearby Trisuli River and its white, river-washed boulders out of town, connecting the city to the capital, Kathmandu, 126 miles to the east. By a rather remarkable orographical fluke—the combined interaction of the area’s mountains, valleys, and the resulting paradise-like subtropical weather systems—it’s also one of the best places in the world to go paragliding. Nearly every day of the year dozens, if not hundreds, of paragliders can be seen floating overhead—brightly colored, downward-curving crescents carving wide, deceptively lazy-looking circles in the sky.

In the daytime the narrow streets are filled with buses and trucks, cars and motorbikes—the squawk of their horns, the belch of exhaust—bicycles, pushcarts, horses and wheelbarrows, dogs, chickens, children, and trash, and tourists taking pictures of it all. In the morning, when the roads are quiet, before the sun is high and disperses the fog that settles in the valley each night and often lingers to midday, shopkeepers stoop in front of their open-air stores with short-handled brooms, sweeping the night’s dust into the street. Some will later ask the foreign tourists who walk by on their way to Lakeside, on the north end of town, to “sponsor” them for a work visa out of the country, already knowing the answer (no), but still hoping, trying to escape the tourists’ paradise.

Lakeside is a single street, a little over a mile long, that houses nearly all of the local adventure tourism companies, the most profitable businesses in town. They sell everything from guided trekking and rafting trips, to kayak and bike rentals, to tandem paragliding flights in which a trained vulture lands on a paying customer’s outstretched arm in the sky. Most of the buildings have new-looking signs featuring large, color photographs of bright orange, red, and blue paragliding wings in flight, framed by the white teeth of the Annapurnas. Other displays feature smiling customers rafting, biking, hiking—sometimes even rappelling off waterfalls. In many places kayaks—old sun-bleached models, never new—line the sidewalks, blocking the footpath. Between the outfitters are restaurants with English-speaking waiters and signs that advertise American and Italian food (AMERICAN BREAKFAST! FIRE WOOD PIZZA!). The remaining structures are Westerner-friendly hotels that offer hot water, “expensive” $3.50 beers, and sit-down toilets. Foreign tourists call it the nice part of town.

At the end of Lakeside, on the left as one walked north toward the mountains, across the street from the Pokhara Pizza House, was the office of Blue Sky Paragliding, one of seventeen paragliding companies in the city. A large, hand-painted picture of Hanuman—a holy, flying monkey god and a popular member of the Hindu pantheon—adorned the sign hanging over the entrance. Propped up on an old tree stump out front stood a 6-foot-tall (fake) yeti, welcoming guests—mostly from Europe.* An old rooster crowed out back.

It was November—one of the two best months of the year (the other is December) for paragliding in Pokhara—and the Blue Sky Paragliding shop was busy. A man standing in line at the counter waited patiently to ask his question. It was the same question he had been asking all over Lakeside the past two months, at each of the paragliding shops, leaving repeated messages on their voice mails and sometimes even stopping strangers in the street to ask it.

He was tall for a Nepali: 5-foot-5. His boots were well worn beneath his faded black leather pants and brown leather motorcycle jacket. An army-green fighter pilot helmet, emblazoned with the red star of China, was tucked under his arm. He was not a communist; he simply liked the look of it. His eyes were dark brown and intelligent. On his chin sat a medium-length, well-kept goatee, and he had an impish grin.

The young man working on the other side of the counter was clean-shaven and short, even for a Nepali. Strong, but boyish looking. “Hello,” he said, his eyes also brown, but liquid and bright—gleaming like a child’s. “My name is Babu.”

The man in the motorcycle jacket quickly flashed a broad, white-toothed smile. “My name is Lakpa,” he replied. “I’m looking for a secondhand wing.”

Babu actually knew the stranger, and Lakpa knew Babu. They had, in fact, become friendly acquaintances on a rafting trip a year earlier. Babu, a lower-caste Sunuwar, was guiding the trip, and Lakpa, a relatively high-caste Sherpa, was on holiday, sent by his employer as a perk. They hadn’t seen each other since.

Babu knew all too well how hard paragliding wings were to come by in Nepal—typically having to be bought from visiting foreigners to avoid the government’s roughly 200 percent tax on all imported goods (hence all the old kayaks lining the streets of Pokhara). But what he heard next made him wonder if he should actually tell Lakpa he had an extra one, let alone sell it to him.

“I crashed mine into a tree, flying in the Solu-Khumbu,” Lakpa said, still smiling. “I work as a climbing sherpa there, and I’m looking for a new one.”

The Solu-Khumbu area, which lies just to the south of Everest in northeastern Nepal, is a

dangerous place to fly, even for an experienced pilot. Babu knew this. It’s filled with powerful updrafts and crosswinds, amidst some of the highest mountains in the world. Towering black cliffs line deep, narrow valleys covered in bristling conifers. There are plenty of hard, sharp places to crash into, which is the reason that people don’t generally fly there and that the ones who do tend to get hurt. Babu had no idea whether Lakpa was an expert pilot or not. He could just be an idiot, he wondered.

“You didn’t break anything?” Babu asked, a little surprised that Lakpa hadn’t died. “Never do that again,” he suggested warily, and then he recommended they take his old beginner wing out ground handling. That is to say, unfold it and see if Lakpa knew which end was up.

Neither of them knew the other was also thinking about flying off the top of the world’s tallest mountain soon—or the other’s remarkable backstory.

Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa was born in Pokhara in 1976. His parents, Nima Nuru and Nima Phuti Sherpa,* who share a first name that means “Sunday” in English, named him Lhakpa,† or “Wednesday”–—after the day on which he was born. Lovingly, they gave him the second name of “Long Life,” or Tsheri.‡ A few years later, before Lakpa can even remember, they moved their family, including Lakpa’s two older sisters, Nyima Yangji and Jangmu Lhamu, back to the family farm in Chaurikharka, south of Everest, where they soon had Lakpa’s younger sister, Nyima Doma.

Chaurikharka is a small mountain village in northeastern Nepal, tucked into a green, forested hillside beneath the towering white peaks of the Solu-Khumbu region. Like all of the small villages in the remote 425-square-mile valley, it doesn’t have an inch of paved road. There are no buses or cars. No bicycles. Everything from potatoes to the toilets that are brought in for the tourists that come to see and sometimes climb the surrounding mountains must be carried in on foot or by yak along narrow, well-worn paths through the mountains.

Before the Himalayan Trust§ built the airport in nearby Lukla in 1964, the only way in or out of Chaurikharka had been a week’s walk through the mountains to the nearest road in Jiri. Today, it’s a thirty-minute light jog to Lukla, followed by a forty-five-minute hair-raising small plane ride to Kathmandu, taking off from what The History Channel officially labeled in 2010 as the most dangerous airport in the world. Still, there are no roads.

Lakpa’s parents’ home, like nearly all of the structures in the village, was made of uneven stones, plucked from the terraced fields on which his family farmed. A small stand of evergreens behind the two-story building offered some semblance of shade from the afternoon sun. Inside, over a high wooden threshold, on the first floor, was a low-ceilinged windowless room, filled with sacks and baskets brimming with potatoes, turnips, cornmeal, and dried yak and dzo dung (used in place of limited wood resources for fires). Up a short wooden ladder was a single, long room with wood plank floors, lined with benches for sitting or sleeping, and shelves filled with bright copper kettles. Narrow windows with whitewashed frames and no glass let in beams of sunlight to the space. It was a good, relatively wealthy home to grow up in, by Nepali standards.

As soon as Lakpa was old enough to attend school, he began skipping it. The thick forests covering the hills along his walk to the schoolhouse in the village center provided a convenient hiding place for his frequent truancies, where in lieu of his studies he enjoyed climbing trees. Sometimes his young friends would join him, and they would build small fires to cook the potatoes they stole from nearby fields. They ate them plain, roasting them first on the glowing coals, pulling them from the fire with bare hands, laughing. He and his friends got in trouble for this, of course, but Lakpa discovered early on that he “learned more from being in nature than sitting in a classroom,” as he would later say.

When he wasn’t working on the family farm, Lakpa liked to spend his free time riding his uncle Dawa’s horse. It was a red, useful animal. And, like all of the beasts of burden in Chaurikharka, it was allowed to roam free through the village because there are no fences. On account of this, the horse would often wander where it was not supposed to go—namely, into the forest. It was during these wanderings that Lakpa and Kili—Lakpa’s older cousin by more than ten years, and Dawa’s son—would be sent to retrieve it. The two boys, easily finding the red horse nibbling blithely on the green undergrowth nearby, would then ride it as fast as they dared bareback into town. It was Lakpa’s first taste of speed, of which he never tired.

It was also during these early years that Lakpa and Kili’s climbing careers started—on a boulder in the middle of a potato field. The large, black-gray stone, located on Uncle Dawa’s farm, was only a few minutes’ walk from Lakpa’s family’s house. One side of the boulder, gently sloping toward the ground, allowed even a child to simply walk to the top and back down again. The opposing side of the massive rock, however, formed a steep, textured wall nearly 20 feet high and required some technical climbing skills to surmount. Uncle Dawa, an experienced mountaineer and professional high-altitude worker who has been on expeditions all over the Himalaya, including Everest, bored holes into the top of the boulder with a hand drill. He placed three bolts into the rock and then promptly showed the two boys their first climbing anchor, using local hand-braided ropes. It wasn’t long until all the young boys in the village were spending the dying light of each day climbing Uncle Dawa’s rock, barefoot, with old retired climbing harnesses no longer seen as safe to use for Dawa’s paying clients.

It was all good fun for the children, but it wasn’t just for fun. Few things are for children in Nepal. Climbing is big business in the Solu-Khumbu, and nearly all of the children who started climbing on Uncle Dawa’s rock knew that they too would one day work in the mountains as sherpas, climbing for their livelihood, Kili and Lakpa included.

Although the term sherpa with a lowercase s is typically used by mountaineers as a job description for someone who carries loads at altitude for a fee, Sherpa is also an ethnicity—like Arab, Anglo-Saxon, or Aztec. Originating in the Kham region of Tibet and traditionally devout Buddhists, ancestors of the oldest Sherpa clans were eventually run out of their homelands in the thirteenth century by confrontational, catapult-wielding Mongols. And then again in the sixteenth century by a group of similarly disgruntled Muslims, finally settling down beneath the shadow of Everest in the remote Solu and Khumbu Valleys of Nepal. Immigrants continued to flow out of the mountains from the north, driven from Tibet by famine, disease, war, the usual—all of whom gradually assimilated into the Sherpa community, creating even more clans, each with its own unique culture and, oftentimes, dialect.* Nepal’s most recent census in 2011 actually considers Sherpa to be a self-reported ethnicity. That is to say, any Nepali can claim to be one. The same census also notes there are approximately 102 different ethnicities within Nepal that speak about ninety-two different languages among them, not including the myriad different dialects of each language.

According to the 2011 survey, there are approximately 150,000 self-proclaimed Sherpas in Nepal who, even at this generous estimate, make up less than 1 percent of the country’s total population. And despite the common use of the term sherpa to describe nearly everyone working as a porter or guide in the Himalaya, very few of them actually serve as porters or guides, unless, of course, they live near Everest. The desire of foreigners to come and climb the tallest mountain in the world, and their seemingly inexhaustible willingness to spend a lot of money while doing it, has become a reliable cornerstone of the Solu-Khumbu Sherpas’ economy—the other being potatoes,† which are not nearly as lucrative, or deadly.

Since foreigners first started climbing in Nepal in the late nineteenth century, over 174 climbing sherpas have died while working in the country’s mountains. At least as many sherpas have been permanently disabled by rockfalls, frostbite, and altitude-related illnesses like stroke and edema while on the job. According to a July 2013 article in Outside magazine, “A sherpa working above Base Camp on Everest is nearly ten times more likely to die than a commerci

al fisherman—the profession the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rates as the most dangerous nonmilitary job in the United States—and more than three and a half times as likely to perish than an infantryman during the first four years of the Iraq war.”

The Khumbu climbing boom, as it were, started over 100 miles to the east in Darjeeling, India, in the late 1800s, when Sherpas began migrating there to look for jobs. The first British mountaineering expeditions headed to Mount Everest in the early twentieth century—traveling through northeast India and Tibet, because Nepal was closed to foreigners until 1949—hired Sherpas to carry their things. It was to become an enduring standard for every future climbing expedition in the Himalaya. Even today.

Originally tasked with toting the enormous amount of supplies needed—or that was thought to be needed—for the early military siege–style expeditions, which tended to measure their equipment in tons rather than pounds or kilograms, let alone ounces, the Sherpas quickly proved themselves exceedingly practical, strong, and apparently more than willing to suffer horribly for what the Europeans considered a small amount of money. They carried eighty-plus-pound loads up to 18,000 feet, without complaint. They slept outside in subfreezing temperatures under boulders. Some of the women brought their babies while working, carrying loads for the foreign climbers. Their employers commended them for being “cheerful,” regardless.

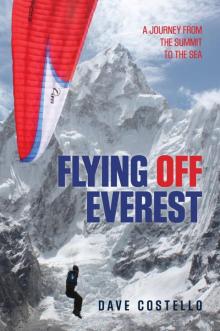

Flying Off Everest

Flying Off Everest