- Home

- Dave Costello

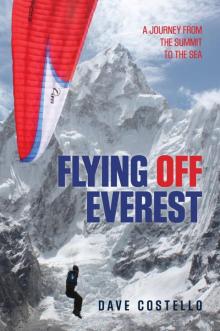

Flying Off Everest

Flying Off Everest Read online

FLYING OFF EVEREST

A Journey from the Summit to the Sea

DAVE COSTELLO

Copyright © 2014 by Dave Costello

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Map by Melissa Baker © Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Editor: Katie Benoit

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Melissa Evarts

Library-of-Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0915-2 (epub)

Advance Praise for Flying Off Everest

“As Babu, Lakpa, and Costello so eloquently illustrate, you don’t need oodles of sponsors, money, or gear to pull off your wildest dreams, no matter how zany. All you need is the uncompromising desire to see them through.”

—EUGENE BUCHANAN,

AUTHOR OF BROTHERS ON THE BASHKAUS

AND FORMER EDITOR IN CHIEF OF PADDLER MAGAZINE

“Flying Off Everest features two dirt-poor Nepalese lads who are impossible not to root for as they attempt a ridiculously bold and unrealistic adventure. Along the way we learn lots about Nepal, Everest, Sherpas, and more. Costello, a serious outdoorsman and a skilled journalist, tells us how they reached the highest point on earth and why they were so determined to fly and paddle to a destination beyond the wildest dreams of most of us. An inspiring tale that happens to be a great read.”

—JOE GLICKMAN, AUTHOR OF FEARLESS

“A book worthy of inclusion in the travel-writing pantheon.”

—JEFF JACKSON, EDITOR OF ROCK & ICE MAGAZINE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The people and events portrayed in this book are real. All descriptions are based on photographs and/or video, site visits, and interviews with the individuals who were actually present during the events described. Interviews were conducted with witnesses separately and, when possible, together. When multiple versions of a story existed, I chose the interpretations that best fit the verifiable facts. I have tried to be clear, within the text itself, what is speculation and what supports that speculation. All direct quotes and dialogue came from either recorded interviews or film footage from the actual expedition. No one included in this book was asked for exclusivity to his or her story.

CONTENTS

Copyright

Dramatis Personae

Prologue

Part I: The Ascent

I: Small Child

II: The Flying Sherpa

III: The Learning Curve

IV: The Ultimate Descent

V: Peak XV

VI: Walking Slowly

Part II: The Descent

VII: In Flight

VIII: River of Gold

IX: Mother Ganga

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Index

Photo Insert

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Listed alphabetically by first name

Alex Treadway—Freelance photographer/videographer for National Geographic Adventure.

Balkrishna Basel (Baloo)—Babu’s friend; trekked paraglider to Everest Base Camp.

Charley Gaillard—Owner of the Ganesh Kayak Shop, expedition sponsor.

David Arrufat—Swiss paragliding pilot, owner of Blue Sky Paragliding, cofounder of the Association of Paragliding Pilots and Instructors (APPI), expedition sponsor.

Hamilton Pevec—American filmmaker, editor/director of Hanuman Airlines.

Kelly Magar—Co-owner of Paddle Nepal, Nim Magar’s wife, expedition sponsor.

Kili Sherpa—Owner of High Altitude Dreams, Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa’s cousin.

Kimberly Phinney (Ruppy)—American fashion designer, expedition sponsor.

Krishna Sunuwar—Babu’s younger brother, expedition safety kayaker on the Sun Kosi and Ganges.

Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa—Babu’s expedition partner, mountain guide, sherpa.

Madhukar Pahari—Expedition support raft oarsman on the Sun Kosi, Paddle Nepal employee.

Nim Magar—Co-owner of Paddle Nepal, expedition sponsor.

Nima Wang Chu—Expedition sherpa, trekking guide.

Pete Astles—British professional kayaker, expedition sponsor; shipped paddling gear from the United Kingdom for use on the expedition.

Phu Dorji Sherpa (Ang Bhai)—Expedition sherpa, trekking guide.

Resham Bahadur Thapa—Expedition safety kayaker on the Sun Kosi.

Ryan Waters—American climber/mountain guide, owner of Mountain Professionals; shared Base Camp with Babu and Lakpa’s team.

Sano Babu Sunuwar (Babu)—Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa’s expedition partner, paragliding pilot, kayaker.

Shri Hari Shresthra—Expedition cameraman.

Susmita Rai—Babu’s wife.

Tsering Nima—Owner of Himalayan Trailblazer, expedition sponsor.

Wildes Antonioli (Mukti)—David Arrufat’s girlfriend.

Yanjee Sherpa—Lakpa’s wife.

From where the water begins, at the supreme source, to where it divides into egos and has separate names; to where the water unites with all rivers to become one with the ocean.

—SANO BABU SUNUWAR

And this I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world.

—JOHN STEINBECK, EAST OF EDEN

PROLOGUE

The Northeast Summit Ridge of Mount Everest,

May 21, 2011—28,896 feet

A step forward there is a 10,000-foot drop into Tibet. Two men stand on a small patch of snow, looking down the North Face of Mount Everest. Waiting. Heel to toe. Connected at the waist by a pair of carabiners. They say nothing, listening to the wind whistling in their ears. Behind them lies a fluttering red and white nylon tandem paragliding wing, and another cliff. The 11,000-foot Kangshung Face. They know that jumping off the top of the world will mark only the beginning of the much longer, more audacious journey that they have planned all the way to the sea. And that flying off Everest in what is essentially a large kite should actually be the easiest part.

Lakpa, who is standing in front, nearest to the edge, looks at his watch. It reads 9:40 a.m. He and his climbing partner, Babu, a professional paragliding pilot and kayaker who has climbed only once before now, have been on top of the world for over an hour. They have not slept in two days. Standing at the edge of the troposphere, their oxygen-deprived brains are struggling to stay conscious—let alone think clearly about launching a paraglider at roughly the cruising altitude of a jetliner. Wearing crampons. The few, strained mouthfuls of warm noodles they forced themselves to eat the night before at Camp IV on the Southeast Ridge have long since vanished. However, they are not hungry. Above 26,000 feet, in the “Death Zone,” where life cannot sustain itself for more than a few days, at most, their bodies prefer to eat themselves.

Babu, a head shorter than Lakpa and standing directly behind him, is praying, dressed in a red and blue full-body down suit, an old, orange, sticker-encrusted helmet on his head. They need the wind, which is gusting up to 30 miles per hour, to stop. For just twenty minutes, Babu suggests quietly to the heavens. It’s how long he estimates they will need to fly off the mountain, down to the airstrip at Namche Bazaar, 18 miles and 17,743 vertical feet away.

Lakpa, wearing a yellow-orange and black one-piece down suit and an old blue skateboarding helmet decorated with a sticker of the Nepal

i flag, is having difficulties breathing. His head is reeling. His vision is dimming. Later, he will describe this moment as “critical.” For now, though, he tries not to fall over. They are down to one bottle of oxygen, which Babu is inhaling at a rapid rate. Lakpa, who has summited Everest three times before now, has turned Babu’s regulator on full flow. He figures it will be best for both of them if his friend stays as conscious as possible during the flight. Babu is the pilot, after all. And Lakpa can hardly fly a paraglider, even at low altitude. He just started learning to fly.

Allowing his gaze to drift over the horizon as he prays, Babu can feel the hard granules of icy snow blowing in the wind, hitting his face. Clouds roll slowly through the lesser mountains to the north. The air above is flawless cobalt.

A white ocean under blue sky.

Nima Wang Chu, one of only two young, high-altitude sherpas hired to help carry loads for the small, four-man, all-Nepali climbing team, sits unroped close to the other side of the narrow, gently sloping Northeast Summit Ridge. A few feet of overhanging corniced snow separates him from an abrupt descent down the Kangshung Face. He is clutching the nylon wing attached to Lakpa and Babu to the ground, trying his best to keep the 51-foot sail from catching in the wind. A low-altitude trekking guide back home in the Khumbu Valley, he also has been climbing only once before now. Phu Dorji (called “Ang Bhai”), the other young climbing sherpa in the group, is just a few yards farther down the ridge, crouching behind a boulder and holding a small video camera. He’s the only one in the group attached to a rope—and likewise has no technical climbing experience.

The team only has enough food and oxygen left for two of them to make the two-day return journey to Base Camp. Unless the wind stops, Babu and Lakpa will have to descend without the aid of supplemental oxygen and face the inevitable bottleneck of climbers, guides, and sherpas climbing and descending on a “nice day” above Camp IV on Mount Everest.

They also think they will lose their chance to become the first people to paraglide off the summit of Mount Everest, the goal that had prompted them to plan their expedition in less than six months in the first place.

What Babu and Lakpa don’t know is that the feat that they think they’re about to attempt, and claim for Nepal, has already been done. Twice. A simple online search using the keywords “paragliding off Everest” would have told them about French paragliding pilot Jean-Marc Boivin’s initial record-setting solo flight from the summit in 1988, as well as the French couple Zebulon and Claire Bernier Roche’s successful tandem flight from the top of Everest in 2001. However, Babu and Lakpa didn’t do an Internet search before climbing the world’s tallest mountain and paragliding off of it. They’ve never heard of Boivin or the Roches.

Back on the summit, forty-two-year-old Benegas Brothers expedition leader Damian Benegas watches the unlikely Nepali crew prepare for their flight, along with his two clients: ESPN Latin Ad Sales executive Leonardo McLean and Argentinian climber Matias Erroz. Each of them has extensive high-altitude mountaineering experience on nearly every continent. And each has paid approximately $65,000 to be a part of the first all-Argentinian climbing team to reach the top of Everest, which they accomplished that morning—with the help of hired sherpas.

None of the climbers on top of Everest that day have any idea that, after flying off of the summit, the two Nepali men standing on the ridge in front of them are going to continue on to fly south across the Himalaya and kayak nearly 400 miles on the Sun Kosi and Ganges Rivers out to the Bay of Bengal. That it will take them over a month. That they will be arrested, robbed, and nearly drowned. Repeatedly.

Then, as if on cue, the wind stops.

It’s the tremendously unlikely, and likely brief, break in the weather that they’ve been waiting for—and desperately counting on—for over an hour. Babu barely has enough oxygen left to last the flight. “No problem,” he says to Lakpa, smiling. He imagines himself somewhere else—a green, grassy foothill near his home in central Nepal, with a warm, gentle breeze—and signals for Nima Wang Chu to lift the wing.

“Run,” he tells Lakpa. Firmly. Without yelling.

They both know they are either going to fly off the mountain or die.

PART I

THE ASCENT

I

Small Child

Ramechhap District, Eastern Nepal,

April 1999—Approximately 1,668 Feet

It appeared suddenly, like an animal moving toward him along the road. Fast. A long, lingering trail of dust rose from its tracks. Enormous, unlike anything the boy had ever seen. A loud, constant rumble echoed through the mountains. Like rocks falling, which never stop, he thought. Then he saw the people inside.

“Oh, shit,” Babu said.

Fifteen-year-old Sano Babu Sunuwar didn’t realize it was the bus that would take him to Kathmandu. He had never seen a bus before. He had never seen anything with wheels. Not even a bicycle. It was the first time he had stood on the side of a road. Anywhere. He was barefoot and carried no bag. Everything he owned was in his pocket: 500 rupees—about $5—given to him by his father a few days before, after Babu graduated from tenth grade, the highest level of school offered anywhere near his family’s village. It was a three-day walk along the river back to his home, which he had never left before, until then. This was also the first time he had had money. Ever. His friend, standing next to him, who had been to the capital city once before and had promised to help find him a job there, prompted him to get on the bus and hand over his newfound wealth to the man collecting fares. The fare collector gave him the equivalent of $2 back. It was a four-hour ride through the mountains to Kathmandu on a single-lane dirt road.

Babu was running away. To what, he wasn’t sure.

He was born the eldest of two sons on May 30, 1983, just south of Everest and the Solu-Khumbu region in the remote eastern Nepali hill village of Rampur-6.* Babu’s first name, Sano, means “small” in English. No one calls him this, though he has always been small, even at birth. Because of his bright, happy brown eyes and contagious toothy grin, his friends and family quickly took to calling him by his middle name, Babu, which in Nepali is a term of endearment for a young boy or “child”—even once he was no longer a child. His surname, Sunuwar, denotes his family’s ethnicity. Completely separate, but vaguely similar to the nearby Sherpa clans to the north, the Sunuwar are part of a larger ethnic group known as the Rais, whose origins lie in Mongolia but who have their own unique language and religion, predating both Buddhism and Hinduism. Farmers and fishermen, they have carved a life for themselves out of the forested foothills beneath the mountains for thousands of years, hand-digging row upon row of narrow terraces to grow rice, millet, and barley, casting their hand-stitched nets into the white rivers that flow and rage beneath the world’s tallest mountains.

The village of Rampur-6 sits along the banks of the Sun Kosi River, high on a ridge. The river below is deep and wide, and blue green, except during the monsoon, when it swells over its banks, churning dark orange-brown, thick with alluvial silt. The hillsides, rising steeply from either side, are covered in a dense green forest. Blue pine, juniper, fir, birch, rhododendron, bamboo, barberry. The jungle teems with thars, spotted deer, langur, monkeys, mountain foxes, and martins. Blood pheasant, red-billed and alpine chough, and Himalayan monal. Snow leopards prowl higher in the mountains to the north, above the snow line, hunting blue sheep.

Six miles to the west, the Tamba Kosi finds its end after tumbling out of the high Himalaya at the mouth of a deep canyon. To the east lie the confluences of the Likhu Khola, the Majhigau Khola, and the infamous Dudh Kosi, the highest-elevation river in the world, which crashes through the mountains from the base of Mount Everest at a rate of roughly 600 feet per mile.

A narrow dirt path winds down around the ridge to the bottom of the pine forest, where a small creek flows into the broad, swiftly moving river. The path picks up again on the other side of the current, zigzagging its way up and over the adjacent hills into t

he next valley. During Babu’s childhood there were no bridges, no roads.*

The home he ran away from was, essentially, the same as all of the others in Rampur-6. A thatch roof covered a narrow, two-story structure held together with logs, rope, and dried mud. Half was built with uneven stones collected from the terraced hillsides below. The other half was open to the air, a simple covered wooden platform that served as a sort of deck and an extension of the house, which, in effect, nearly doubled its size. The first level had three walls and a dirt floor and acted as the family’s barn. Cows and goats ruminated in the shade on grass grown on the steep hillside below, brought up the ridge for them by foot, usually by Babu. Up a short ladder was a small, windowless room—the family’s main living area. There was a shallow recess in the floor for cooking fires, but no chimney. The smoke collected thickly on the ceiling. A doorless doorway led out to the second-story platform, which was covered by the thatch roof and open on three sides. Hay dried slowly on a head-high wooden rack. There were no chairs, no furniture. Listless bent dogs and thin chickens wandered aimlessly outside.

Babu’s father was a fisherman. Early each morning he would walk forty-five minutes down the ridgeline to the river, where he would fish, often until dark. He taught his son how to swim in the cold waters of the Sun Kosi, how to move with the swirling currents and survive in a whitewater rapid, should the boy ever find himself unfortunate enough to fall into any of the surrounding rivers. Young Babu loved it, however, and soon began swimming the nearby Class IV* rapid with his friends, but without a personal flotation device (PFD)—on purpose. It was one of the few things he and the other boys his age did for fun. “Everything else was for survival,” Babu says. “Not fun.” At the age of twelve, he watched one of his friends drown while swimming in the rapids. Babu continued swimming.

Flying Off Everest

Flying Off Everest