- Home

- Dave Costello

Flying Off Everest Page 2

Flying Off Everest Read online

Page 2

As a child Babu was kept busy carrying hay for the cows and goats up the steep ridge from the terraced fields that his mother and he tended while his father fished. He watched after the animals as they grazed in the forest, and he completed a long list of other daily tasks that go along with subsistence living in the mountains in Nepal. If he didn’t do his chores, his mother didn’t feed him, he says. Two meals a day of either fire-roasted fish or dal bhat, a spicy rice and lentil dish with roasted potatoes, and sometimes yak meat or beef—usually not.

After completing his morning chores, collecting milk and carrying hay, Babu would walk to school. It took him twenty-five minutes to get to the small, government-funded Level 1 school in his village. It offered classes up to Grade 3. He attended whenever he could, when his parents didn’t need his help at home, which was rare. After completing third grade, young Babu started making the forty-five-minute trek to the nearest Level 2 school. His main goal was to learn how to read and write, which proved difficult in a school with no books. After completing sixth grade, it was an hour walk each way to his Level 3 school, which went to eighth grade. No lunch was offered during the day. He ate in the morning and at night, if he finished his chores. And that was becoming increasingly difficult with his now two-hour walking commute to school. The nearest Level 4 school, the highest offered, was in a neighboring village called Dudbhanjyang, across the river and over a small mountain.

Babu crossed the Sun Kosi Monday through Friday just after dawn on an old, inflated tractor tire inner tube that had been carried in from the nearest road, a three-day walk away. He didn’t even know what a tractor looked like. It took three hours, one way, gaining and losing 1,000 feet of elevation in each direction. He carried a notebook and a pencil, supplied to him by the school. The high school itself, which sat on top of a similarly narrow and inconveniently accessible ridge in the next valley, consisted of two long stone buildings covered in cracking white plaster, with red wooden roofs and cold, bare concrete floors. The windows held no glass. The teacher would have to close the red wooden shutters to keep out the wind and rain, making the classroom, lacking electricity, eerily dark. Unlike most of his classmates, whose parents often kept them at home to help with farming and chores, Babu managed to complete tenth grade, the final year offered, at the age of fifteen. He knew how to read and write in Nepali, making him one of the 54.1 percent of Nepalese who could at the time.* And yet he had nothing to read.

The idea to leave the village came from the river. Standing on the riverbank or high on a ridge, doing his chores or walking to and from school, Babu often saw strange things float past, bobbing in the waves. They would always be brightly colored. Blue. Red. Yellow. Green. The floating things were odd, he thought, but it was the people on top, or sitting inside of them, that captivated Babu’s imagination the most. They were kayakers. Whitewater rafters. Foreigners with light-colored skin who spoke strange languages. English. Chinese. French. He didn’t know anything about them, other than that they came from upriver somewhere and went downriver to … well, somewhere else—someplace far from where he was. “That’s all I knew,” he says. He would watch them from his family’s house, as they rested on the riverbank below, drying wetsuits, napping, playing games in the sand. He imagined what it would be like to be one of them. Not having to milk cows and goats each morning. Not having to carry hay or walk three hours to school each way. To just step into the river each day with a small, happy-colored boat with a big stick, and float downstream to something new. Playing in the water. Following the river. That must be a good life, he thought. Maybe the best life. Certainly better than the one he was living at the moment, he thought. So Babu began to dream of kayaking and a new life of adventure.

When Babu graduated from school, his father gave him some money to attend the graduation feast put on each year by the high school in Dudbhanjyang: 500 rupees. It was the first time Babu had ever had money in his possession. He knew the small wad of papers that his father pressed into his hands was an opportunity, though. And not just an opportunity to eat well and get drunk, which was the intended purpose. It was his ticket out of the hills, a chance at a new beginning, one without goats or cows or the job of carrying hay. Perhaps even a chance to go kayaking, he thought.

Babu consulted an older friend who had made the trip out of the hills once before and had returned after working for some years in Kathmandu, the country’s capital. They made a plan, which started simply enough with walking into the hills and out of the village, without telling their parents. Away from everything Babu had ever known. Then, they would catch this thing called a “bus,” his friend told him, that would take them to the city. Babu would learn how to kayak—somewhere, somehow—and convince somebody to pay him for it. A few days later, when it was finally time for the graduation feast, they said good-bye to their families, without telling them of their plan; crossed the wide blue-green river using the old inner tubes left on the bank for the purpose, past the dirt trail that led up the opposing hillside to Dudbhanjyang and their graduation party; and kept walking westward over white stones. Three days through the forest, along the river to the road.

Babu knew it was not a safe time to be traveling. Nepal was three years into a civil war. People left their villages only if they had to, because when they did, they tended to disappear.

On February 13, 1996, when Babu was just twelve years old, members of the Communist Party of Nepal attacked police posts all over the country. The guerillas, led by a man named Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who called himself Prachanda, killed the officers and took their weapons, hoarding them for future attacks in what he accurately anticipated was going to be a long, bloody struggle for control of Nepal. It was the beginning of what would turn into a horrific ten-year civil war—“the People’s War,” Prachanda called it. The conflict would eventually cost more than 12,800 lives and displace over 150,000 Nepalese from their homes. The economy crashed. Unemployment reached nearly 50 percent, the country left, for all practical purposes, in ruin.

For hundreds of years, ten generations of the Shah dynasty had ruled Nepal, as either an absolute monarchy or a constitutional monarchy, constitutionally immune to prosecution. The Maoists, Nepalis loyal to the now infamous Communist Chinese revolutionary/tyrant Mao Zedong, claimed that Nepal’s rulers had failed to bring genuine democracy and development to the people of Nepal, which was true. In the eighteenth century, members of the Shah family had cut off the lips of their challengers. A hundred years later, they were dropping uncooperative subjects down wells. More recently, a member of the royal family had allegedly run over a musician on the street with his Mitsubishi Pajero. The man hadn’t played his request.

The day-to-day economics and development of Nepal also hadn’t gone so well for the Shahs. By 1996, 71 percent of Nepal’s population was living on less than $1 a day—absolute poverty. More than half of the people in Nepal were illiterate. And foreign debt accounted for at least 60 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Even today, Nepal is still listed as one of the twenty poorest countries in the world by the United Nations, just ahead of Uganda and Haiti.

The communists promised to empower the people, redistribute the country’s wealth, grant women equal rights, and eliminate the Hindu caste system, which had been “officially” adopted by Nepal during a period of absolute monarchy between 1960 and 1990. The Maoists looted police stations for weapons and made homemade explosives, preparing for the long guerilla siege to come. As the conflict escalated they began invading remote villages like Babu’s, which were unprotected by the royal army, barging into classrooms, shooting teachers and abducting the pupils, forcing them to fight as child soldiers. They tortured their opponents and exhibited their mutilated bodies in the streets. They had lost their cause, but continued fighting.

In 2001 the Nepali Parliament passed the Terrorist and Destructive Activities Act, allowing ninety-day detentions and the unapologetically forceful interrogation of known Maoists. King Gyanendra suspended th

e elected government and instituted martial law, effectively controlling the military and the press.

Babu, like most people in the country who scratched a subsistence living off the land, was rightly afraid of both the government and the insurgents. He didn’t know whom to trust, if he must, and that the answer was probably neither the Maoists nor the government. He was on his own, and he knew it.

Once in Kathmandu, Babu’s friend immediately got him a job working in a carpet factory. He spent anywhere from twelve to twenty hours a day, seven days a week, working along with dozens of other teenage boys and girls, sitting in a small, crowded room. According to Babu, his payment was 200 rupees per month ($2), two meals of dal bhat a day, and a space on the floor inside the factory on which to sleep. His friend had gone and had not returned. Babu was alone.

This, of course, was not what he had been hoping for when he had left home. He was accomplishing nothing, he thought. He was frustrated. So after two months of mind-numbing, tedious labor, Babu quit, with almost no money and no place to stay.

Babu slept on the streets in cold, dark corners until he found his next job, working as a bus assistant. This new position required him to stand in the aisle of the bus and collect fares all day, and to clean it each night—sweeping, picking up trash, dealing with belligerent passengers who were unwilling or unable to pay. It was the easiest thing young Babu had ever done in his life, and it paid, respectively, in spades: 500 rupees a month, and 100 rupees per day for food. He ate well: two meals of dal bhat each day, every day. It also afforded him the opportunity to sleep on the bus. After twenty-six days Babu had managed to save over 1,000 rupees ($10), all the money he had earned that he hadn’t spent on food.

He bought a bus ticket back to the nearest road to his village and walked three days along the river home, proud to have doubled the money his father had originally given him for his graduation present. His parents, although glad to see him and more than happy to have the unexpected extra income he gave them, didn’t want him to go back to the city. They asked Babu to remain in the village. Yet, just a few months later, in January 2000, Babu returned to Kathmandu again, this time with no money. His grandfather had needed help herding cows to a neighboring village, and after helping him move the cattle, Babu simply kept walking to the road and caught another bus back to the city. This time he was looking for a job in the tourism industry, which he had learned, during his time working on the bus, was the real moneymaking business to be in. Besides, he still wanted to learn how to kayak. So he went where the tourists go: Thamel.

Located on the north side of Kathmandu, Thamel occupies less than 1 square mile of the city. Yet it is the sightseeing hub of Nepal, housing nearly all of the country’s adventure tourism companies, upscale hotels, and restaurants that serve everything from pizza to steak and apple pie. The streets are narrow, winding, and categorically confusing, built in a time before cars and, evidently, reason. There are no sidewalks. Tucked between old, close-fitting buildings that tower up to seven stories overhead, it’s like walking through a small, urban canyon: more often in shadow than not, even on a sunny day. Crowds of people, scooters, motorcycles, and cars all navigate the tiny alleys, darting beneath innumerable signs covering the walls, directing people to businesses that oftentimes no longer exist. Or perhaps have just moved locations, without bothering to remove the sign from their old whereabouts. Standing in front of their shops, vendors call out to passersby, hoping to lure them into a sale by yelling louder than anyone else. A collective cacophony, advertising everything from a simple loaf of bread to a multiday rafting trip down the Karnali, rises up from the smog. The sound of motorcycle and scooter horns regularly punctuates the dissonance. Small children in tattered clothes and lepers crawling on the ground ask for change, speaking English.

Upon arriving in Thamel, Babu saw some men loading equipment into a line of trucks: backpacks, portable stoves, tents, food. He approached them and politely asked, “Where is this trekking equipment going?”

“Pokhara,” one of the men told him.

Babu had heard of Pokhara before, during his last visit to Kathmandu. He knew that, like Thamel, it was a place tourists often went. And that it was a popular place for whitewater kayaking and rafting in Nepal. At least, that’s what he had heard. He had never been there, and he didn’t know anyone who had been there either.

“Do you need a porter?” Babu asked.

“Have you done trekking before?” one of the men loading the truck probed.

“Yes,” Babu said without hesitating. He knew if he told the truth—that he had never worked as a porter before in his life—they would never take him. He spent the day helping the men load their trucks for the expedition. They gave him no food or water. As the afternoon wore on, Babu began to wonder where he would sleep that night if they didn’t take him along. They hadn’t told him yes, but they hadn’t told him no. He was hungry and thirsty. At the end of the day, when the trucks were finally full and as the sun was setting, one of the men put 20 rupees in his hand. “Thank you for helping,” he said. “But we cannot take you with us. You are too small.” With that, the men got into the trucks and left.

Babu walked to the bus station. He asked the man working at the counter how much a ticket to Pokhara cost. The man told him it was 150 rupees. The last bus scheduled to leave Kathmandu that night departed at 9:00 p.m. and was expected to arrive in Pokhara at around 4:00 a.m. the next day. Unable to afford the fare, Babu waited, watching the people loading and unloading as it grew dark. He watched quietly as the last bus turned on its engine and slowly began to roll away. He looked around. Then, when he saw that no one was looking, he ran and jumped through the door, onto the bus.

Babu found himself seated next to an old man holding crutches. Babu could see that the man had only one leg. He looked ragged and disheveled. Destitute, just like him. The old man, having watched Babu’s desperate leap onto the bus, asked him how much money he had.

“Twenty rupees,” Babu told him truthfully.

“Do you know how much a ticket costs to Pokhara?” the old man asked.

“The counter price is 150 rupees,” Babu admitted sheepishly.

“Yes, yes,” the old man said. “Now here’s an idea: They can see that I have only one leg and will feel sorry for me. But you, you have everything they can see. So if I tell them you cannot speak, you must not speak. When people come to collect money, I will tell them that I have no leg and that you cannot speak.” Babu, having no better alternative, agreed to follow the plan. The bus bumped and swayed on the broken road. Outlines of dimly lit buildings passed slowly through dark, dusty windows.

Babu could see the bus assistant looking at him and the old man, obviously concerned, as he collected fares from the other passengers. Babu had done the man’s job himself, and he knew what was coming.

“Hey, you two,” the young man finally said as he reached their seats. “Where are you going?”

Babu, not actually knowing sign language, raised his hands and wiggled his fingers with imagined meaning. The old man waited a moment for the uncomfortable display to finish, then spoke.

“We are going Pokhara because we have trouble,” he said. “This boy is my friend. He cannot speak. We don’t have money.” The statement hung in the air, shuddering along with the bus as it jostled itself noisily over the cracks in the road. Babu put his hands down.

“You don’t have money?” the assistant asked, alarmed. “Why did you come to Kathmandu then? Why didn’t you just stay in Pokhara?”

“We wanted to come to see our relatives,” the old man said simply. “But we cannot find them. So we have to go back.” The bus assistant thought about this for a moment, considering the difficulties involved with stopping the bus and throwing an old man with one leg and a mute boy out onto the street at night. The other passengers would not be pleased, he knew. He then turned and continued to walk down the aisle, collecting fares, leaving Babu and the old man to sit together in silence.

Through the windows, Babu watched the silhouettes of Kathmandu’s tall brick buildings slowly turn to vague outlines of dark roadside shacks. Sheet metal roofs held down by old discarded tires, rocks, and bricks. The mountains in the distance became distinguishable from the starry sky only by their darker blackness—a series of jagged holes in the horizon. The bus, rattling, climbed steeply out of the valley to the west and then crested over a narrow pass, dropping suddenly, clinging to the sides of the shadowed mountains, turning sharply, back and forth. Switching back on itself as it descended rapidly down to the Trisuli River and into the even deeper night of the valley below.

Hours later, the bus rolled to a stop in the small roadside town of Mugling, the halfway point between Kathmandu and Pokhara. Babu rose stiffly from his seat, exiting the bus for a scheduled thirty-minute bathroom and dal bhat break. The town was dark and still, save the lone roadside vendor who had stayed open to serve the passengers on the last bus to Pokhara that night. The old man with one leg immediately began to beg for food, asking the other passengers to buy him and his young friend a meal. Babu hadn’t eaten in almost two days and so didn’t find it prudent to discourage him.

“Can your friend work?” someone asked, pointing to Babu.

“Yes! Yes! Yes!” the old man replied, ready to volunteer him for any sort of labor that might get them both some food. Babu knew he was too weak and malnourished to work, so he began to wave his hands wildly, making recognizably desperate gestures in the half-light of the bus stop. He placed his left palm up in front of him, like a plate, and mimed the motion of eating dal bhat, pinching the imaginary soggy lentils and rice between his fingers and shoveling them greedily into his open mouth. It was pathetic, he knew, but the display had the desired effect. Babu and the old man ate their free meals quickly and got back on the bus, completely silent.

At 4:00 a.m. Babu stepped down onto the gravel parking lot of the Pokhara bus station for the first time. The city was quiet, the morning air still cool and dark, waiting for the sun to rise and glare off the whiteness of the mountains in the distance. In his pocket he still had the 20 rupees (about 20 cents) he earned helping load trucks back in Kathmandu. Looking around the vacant lot and the surrounding darkness, he realized, suddenly, that he had absolutely no idea where he was, where he was going, or what he was going to do next.

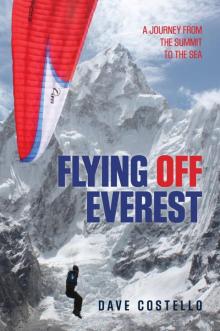

Flying Off Everest

Flying Off Everest